If you’ve ever wondered what Japan is like, you can experience it vicariously through me. I kept copious notes on my experiences there. It was a hard study trip, and I didn’t get nearly enough rest and I was sick the whole time, so I can’t describe the account as peppy, but I think I provide some very engaging insights into Japanese culture and the sort of experiences you might expect if you ever go yourself.

May 28th

What a crazy first day! I couldn’t sleep to save my life the night before my morning flight to LA, where I would catch my flight to Narita. I got up at 1:45am to grab my things and hop in the car, where I drove to the train station.

It’s fascinating how good people are at ignoring other people at 2 in the morning. We automatically create safe distances and keep quiet and still. Or maybe that’s just me. It wasn’t terribly cold waiting for the bus, so at least I didn’t feel hostile. But just before the ATA bus arrived all the airport employees showed up and created a lively, friendly chatter, if you can believe it. The temperature is cool, but it’s damp and it’s still totally dark out, so I had to wonder at their energy. Are they just used to those cool dark mornings?

I arrived at the airport at 3:15am, sooner than expected, and breezed through security. I got to my gate by 3:30am. I got my first premonition of trouble then, when I noticed that a different flight going to LA was cancelled. 30 minutes later, I got a text saying that my flight was cancelled as well. Some curious glitch in the system allowed me to “switch” my flight to the same flight, which had already become the only flight with available seats that would get me to LA in time for my connection to Japan, and I thought, rather optimistically, that the problem was solved. So certain of this was I, that when another girl came up to me to express concern over the cancellation, I suggested she do the same thing I did with the glitch. It wasn’t until 5:30am rolled around that the shut gate and an empty waiting area convinced me that my flight was indeed cancelled. I then waited in line for at least 30 minutes to talk with a harried airport representative who informed me that the soonest flight going to LA was at 1:10pm, and she couldn’t help me with my connection to Japan. After getting on standby, I wobbled back to the waiting area, wrapped my head up with a scarf and wept.

Once I was calmer, I contacted ANA to see about getting my flight moved to the next day. It took at least 30 minutes to get connected to someone. They were happy to move my flight, despite the difficulty of communication (the lady had a heavy accent and my reception wasn’t great), but it would cost me almost $600. I had just under $400 in the bank, which was meant for spending on the trip, but getting there came first. I told the lady that I needed to get the funds together, and could I call back when I was ready, and she said yes, she could make the reservation, but I would need to pay off the change fee before I could check in. Then I contacted my mom and asked for a loan, panicked and humiliated. She, however, was gracious and understanding, lending me the money and not asking many questions, prepared to wait till I was calmer to find out the details. I then contacted my teachers to inform them of my predicament. They suggested getting a flight directly to Japan from DIA, and citing cancellation as a reason to wave the fees and price difference. When I traveled to United’s gates however (after making a time-consuming detour to the A gates), I learned that the flight was already full and United was no more willing to cover the costs of my mistake than Southwest or ANA had been. I returned to my gate to wait on standby, and prayed hard, and I did manage to get on the flight, at the cost of an employee’s seat. On my third call to ANA, with its 30 minute to an hour long wait time, I got a hold of a pleasant lady who couldn’t seem to find the fees I still needed to pay, so I landed in LA under the vague impression that I may have gotten around the fees somehow, but a part of me knew this wasn’t true, since as warned I couldn’t check in online. Everything had yet to be resolved.

Once landed, I made a beeline for United ticketing area, for the pleasant lady had told me I was now on a United flight, but I suspect now that she meant it was a United plane, because when I trekked across the entire airport and found someone who could give me informed answers, it turned out I was on an ANA flight after all. I walked half way back the way I’d come, to ANA ticketing, only to learn that all the ANA employees were already off for the day. I used the automatic ticketing machines to confirm that I really couldn’t check in until I’d paid those fees. My phone was dying, again, so I sat beside the wall, plugged in my phone and settled in for another hour long wait time with the ANA phones. At last, I got a hold of someone who could find those change fees and help me through the process of paying for them. I decided then to get checked in and pass security and spend my night in the airport on the gates side, as that felt a bit safer.

But for all my complaining, God has been so good to me throughout all of this. He kept me strong and reasonable and self-controlled when I wanted to cry (other than the short weepy moments I had in the privacy of my scarf), to scream, to hit something or someone; when I wanted to hate and scorn, when I just wanted to give up and sleep. He got me to LA, provided the funds once again, as he always does, and has put me on the flight to Japan. He’s kept me safe, ensured that I had a pillow and blanket with me, and even let me sleep a little on the plane (a unheard of phenomenon for me, I can tell you). I don’t know why He wanted me on this flight, a day later than planned, or why I needed to be this shaken at the very beginning of this trip, but I know that His plans are good, and He was there for me, providing for all my needs, every step of the way.

May 29th

I had an interesting encounter with a Japanese lady in the airport. I had gotten up after a restless night spent on the benches in front of an airport gate, and needed coffee, so I wandered over to a cupcake stand. As I was paying for my order, the lady with her two small children in tow came up to make her order, and spotted the 10,000 yen bill in my wallet. She asked me as I stood there waiting if I was going to Japan, and I reacted with surprise and a bit too much suspicion to her question, so she very quickly explained that she’d seen the bill. I managed to relax and smile a bit and acknowledged that she was correct in her deduction, and she said that she’d just come from there. I asked if she’d been there for tourism, and she said that no, she’d been there to visit family. It was only at this point that I realized that she looked quite Japanese, and she must have seen the realization dawn on me and the bit of embarrassment I felt, because the conversation suddenly turned to how much we both like macaroons, and then sort of died. I was relieved when my breakfast and coffee came soon after.

May 30th

The train going from the airport to Nippori station has seats that automatically swivel to face the forward direction of the train at the end of the line. I was impressed by this, not so much by the technology itself, but by the attention to detail and the priority given to comfort that was evident in such a design. The temperature is mild, cooler than I expected. On the train, the people aren’t silent, just quiet and controlled. I watched a older gentleman and a younger lady in particular. They talked throughout most of the train ride. At first, they seemed as interested in the sights we were passing as I was, but a few stops down the line they both pulled out phones and seemed to be doing different things on them while still holding a quiet conversation and occasionally showing each other things on their screens. I noticed as we boarded that some people put large suitcases on the overhead racks. It’s common sense not to do that in America, but apparently you can get away with it here. The train ride is incredibly smooth. I can write normally in my preferred tiny font without trouble. The engine barely makes any noise. No screeching wheels, no rumbling tracks, no snapping electricity. I wonder if they just put more effort into sound proofing the train, or if the train really is just quieter by design. It’s also nice that though they have lots of advertisements around, on screens and back of seats, none of them make noise. I’m feeling better now. After an 11 hour flight and the rough night before I had a pretty bad headache, but it calmed down once I met with Kim-sensei. My body is still sore, but I’m so glad to finally be here. Kim-sensei tells me that if I get bumped in a train it’s my fault. I glanced around the train at one point and noticed that every single person who wasn’t sleeping, myself excluded, had their phones out, working or entertaining themselves or what have you.

The airport is apparently located outside of Tokyo proper. Shortly after getting out of the airport property, the scene filled with huge, bright green and fluffy pines, thick undergrowth, vines everywhere, and rice fields, small and scattered, dotting the low lands. The topography seems a bit sudden, with hills shooting up from fields and cities, thickly covered in forests, like frozen green explosions. The undergrowth seems so thick it’s probably impassible. These slowly gave way as we got closer to the center of Tokyo to bigger fields and scattered cityscapes, then, eventually, the thick cityscape of Tokyo, where certain neighborhoods I passed were just bundles of 4 and 5 story houses packed together with seemingly no breaks at all, alleys so narrow it’s a wonder people can walk through them, and streets that barely break the steady stream of buildings that flash past my window. Like in China, nature seems to grow aggressively wherever allowed. As we go along the tracks, every crack in the cement has vines and weeds trying to peek out and there are slots in the walls where they seem to have intentionally allowed the plants to flourish. I like being near so much green, even when in the heart of a metropolis.

People seem very relaxed on this train. Just within 5 feet from me, in various directions, 4 people, including Kim-sensei, are napping in this public but quiet and curiously private place. I don’t know that I could relax that much in a public place, but it is relaxing to be around, at least.

May 31st

I went for a walk this morning. The streets really are narrow, and around Yanaka anyway, mostly one-way, just barely large enough for the little electric cars to buzz down them at 30 to 40 kph. Plants and planters line the streets, decorating otherwise plain entryways with modern gray or rustic brown doors, many of which would require me to duck to enter. So frequent are these little doors, that by the end of the walk the few taller doors I passed started to feel grandiose or even excessive.

A very little door

A typical street in Tokyo, Japan

My favorite cemetery

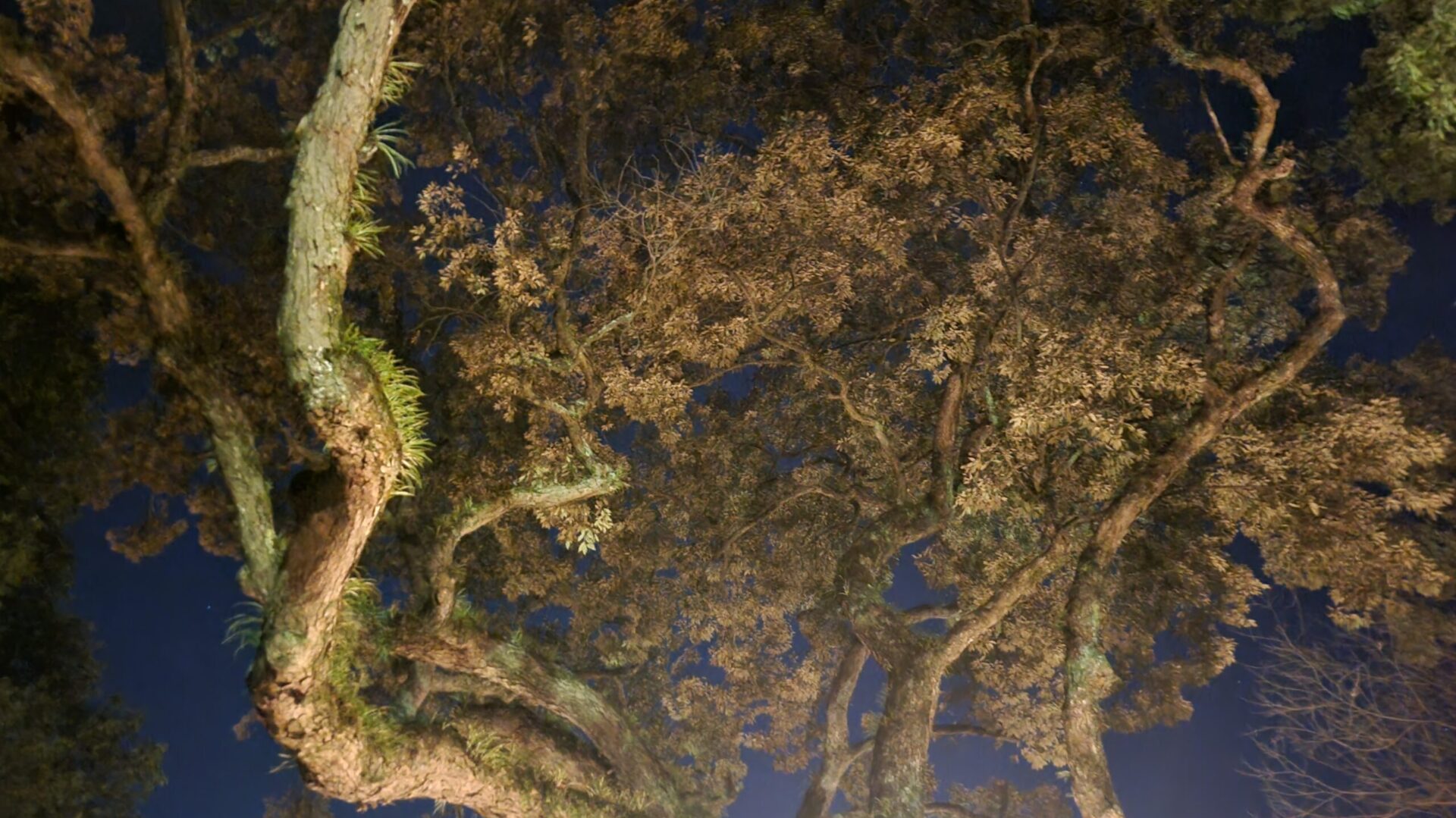

I passed as many as 10 cemeteries on my way to Ueno park. They are pleasant places, quiet, still, with at least one very old tree in each, and fresh flowers scattered among the proud stone blocks piled with controlled chaos in roughly square patterns. Long wooden fence posts stand behind most of the monuments, with elegant kanji painted down their faces. I believe the stone markers represent the family as a whole, while the wooden posts represent more recent individuals or very important persons in that family. In a favorite cemetery of mine, the ancient tree that grows near its center towers over the 3 or 4 story buildings that box in the cemetery on every side. It’s like the city stands guard over this resting place, modern, but respectfully looking away from the preserved ancient. Up the backs of those buildings grow vines bountifully, tying in a natural beauty to the reverent beauty of the cemeteries and the modern beauty of the buildings. Each cemetery provided wooden buckets and scoops for visiting family members to clean off the marble stands, and those usually had small holes for leaving incense and platforms or small depressions for leaving food or drink offerings. I was amused to see several graves with beer standing proud beside the flowers.

Ueno park, rather than being boxed in, seemed to dominate its space, dwarfing the many buildings and attractions found therein. The trees there were also ancient, and the spaces between them seemed vast and devoid of life. Even grass was prevented from growing there. As I got farther in, though, the undergrowth increased a bit, and with it the birds, but it was all carefully controlled. Near the center, I was just in time to see the elders gather within ear shot to exercise to blaring instructions and music from a radio. I walked right through them, seemingly invisible, though people greeted me easily enough on the other paths in Ueno. The radio exercises, vast park with attractions inside, and controlled landscape made me think of the Temple of Heaven, but the people act a little different here. In China, the groups stuck pretty close together, but here people maintained a lot of space, spreading out like a paint splatter across the entire center of the park, often finding more secluded spots with low visibility, as though they craved privacy despite the communal nature of radio exercises.

Ueno’s towering trees

Hydrangea season is the best!

Outside of the park, people were less inclined to great me, though I made eye contact with a lot more people than I was expecting. The only people who actually said good morning were in the park, walking along the paths through the trees just like I was, and nearly all of them greeted me in English, even when I greeted them first in Japanese. As I walked the streets back the way I’d come I noticed that the young business people in particular, especially the men, seemed inclined to ignore me, refusing to make eye-contact even when I stared.

The cars in those narrow streets drive with a lot more confidence than I’d expected, passing with startling closeness to me if I didn’t make an effort to be far out of the way, and driving much faster than I think I’d dare with all those blind spots and pedestrians, but when I actually found myself in their way, they never got aggressive, honking or inching closer, but patiently waited for me to notice and move. The Japanese attitude of enryousuru is a potent thing, I guess.

That morning my group had a meeting to talk about the area, which I found timely and interesting. Around 1970, there weren’t a lot of people here. The locals kept moving away for better prospects and the kids didn’t care about the history here. Around that time a well-known writer visited the area and loved it, using it in her fiction and talking about it to her circles, which kick-started a small tourist industry. The nearby Art University also helped. Eventually the area started catering to the growing number of tourists, inspiring the Yanaka Ginza and jump-starting the local businesses again. It’s on the outskirts of the old Edo. This area is attractive to the common class, rather than the ritzy, “nouveau riche” class that prefer the higher ground and the expensive shopping districts closer to the center of Tokyo.

We then went to Sensouji, with its Kaminarimon, a famous tourist spot in Tokyo. The kaminarimon (lightning gate) is actually the third of a series of gates surrounding a grand Buddhist temple. The road that lies between the third and second gate is called Nakamisedouri, literally “between shop road”, and is lined with tiny shops selling souvenirs and foods and hand-crafted products and anything else you could want. If you turn to the left or the right through the narrow breaks that periodically appear between this line of shops, you’ll discover that the market extends in every direction, countless shops bleeding out into the city surrounding the temple and its gates. Past the second and third gates, I encountered shops that sold more religiously themed products, like Omikuji (fortunes) and Omamori (good luck charms). Past the third gate was the temple grounds themselves, with several more shops selling religious paraphernalia.

The crowds were crazy!

This was my first introduction to the touring school groups in Japan

As I walked up to the temple, I passed a huge iron structure like a well with a roof and sand in the wide dish, where people placed incense sticks and stood near to inhale the purifying smoke.

I walked up the steps to the temple, excessively tall as though made for giant feet, and watched people toss coins into a huge box with bars in the lid. They would toss the coin, clap their hands twice and make their requests, hoping they’re heard. If you went closer you could ring a bell attached to a thick, colorful rope which was intended to awake the gods you were praying to. The religion here has an attitude of “If you want something you have to give something”. Everywhere you go there are Japanese tourists wearing kimono and taking selfies.

Off to the right side, in a square separated by walls and a tall gate stood a shrine. Just inside the gate was a little sign posted in the center of the pathway reminding people to walk on the sides to allow the kami of the shrine to walk in and out through the center of the path, but it was largely ignored from what I saw. The entire square was paved with gray gravel, and this area too had a few shops for religious products, but right around the front of the shrine there were large planters with sparkly white gravel, as though it had been purified. It was much quieter in this little square because there weren’t the crowds that flocked around the grand temple and the shops in front of it.

In front of the shrine were little gardens and rest spots, where people could get off their feet after surviving the masses lining the nakamisedouri, the three gates, and the temple’s steps. They were not quiet, there were far too many people for that, but they at least had a slower paced feel, and the gardens with their carefully controlled look and distinct appreciation for stones and trees, helped me relax a bit. The pigeons around this area are remarkably confident, barely deigning to move when you walked near. I only saw one person tossing them pieces of bread, but given their size and familiarity with people, I suspect that happens often. The weather has been gray and cool all day and a bit windy, though, so I started looking for someplace with a wind break.

I went on from there, moving in the direction of the kaminarimon but behind all the shops, in a back alley, really, and soon encountered a playground. It was surrounded by trees and shops, so the wind was all but gone, and none of the crowds on the nakamisedouri were evidenced here. Most of the time is was quiet, though it was almost never empty. People had a way of passing through there. When I got there a group of young women were hanging out there on one side, mostly talking, while on the opposite side a couple in kimonos were taking pictures and selfies on the steps leading up to another smaller Buddhist temple. I settled on a bench a safe distance from both, with a tall bush behind me which separated the playground from the back alley from which I’d come, and started eating the food I’d brought.

I begin to suspect that the Japanese find it a bit disconcerting when I wander around on my own. They seem to find me easier to acknowledge and talk to when I’m with the group. Like when I was walking around the streets of Yanaka, people mostly ignored me, and I noticed that I was the only one who wandered into that playground alone.

When the couple wandered off and the group of young women went off to go shopping, almost like clockwork a young mother with her two children drifted in. She found a spot on the far side of the playground and let her kids play for a while, but when a group of boys strolled in (they might have been middle school or high school), making much more noise than the previous groups had, she quickly (yet without seeming hurried) drifted back out with her little ones. The boys were the ones who seemed to get the most out of the play set, climbing high on the bars and messing around on the slide and rockers. Just moments after the boys got tired of carousing on the tall metal structure and wandered out the back way, a group of school girls wandered in, talking a lot and playing with the swings a bit. They also chose to hang out on the far side of the playground. That was just the way of it there.

On that far side, a tall tree grows with what looks like little peaches on it. Maybe they’re persimmons? I saw a blackberry bush on my walk earlier as well. The abundance of fruits seemed a bit staggering to one who has lived most of her life in arid deserts. Does anyone eat these fruits, I wonder? The ground of the playground is plain dirt, with tiny stones covering it. The only place that has actual padding is directly below the metal bar structure. It seemed a little strange to me, since I’ve never played on a playground in America that didn’t have padding or mulch and such for protection, but perhaps the kids here are just a bit tougher, or more careful?

I eventually tired of my rest, and wandered through the shops a bit, then returned to the first gate. As I waited for the group in front of kaminarimon, I was astonished once again by the crowds. Around here in particular it was quite bad, not only because there were so many people, but also because they were all standing around getting selfies and pictures of the kaminarimon. Once again, loitering around by myself, I was quite invisible, even though I was actually in good company this time. There were quite a few people doing the same along the bar I was leaning on, facing the gate. But with all eyes fixed on the imposing gate opposite, it’s little wonder.

I noticed a group of young people singing together as they waited for something or someone outside of a shop near the entrance to Sensouji. The shop was a food stand. They young people wore matching school uniforms, though I couldn’t tell if they were middle school or high school. The crowd seemed to be ignoring them, though I passed quickly myself and didn’t see much.

Once everyone had been gathered, we walked from there to the Tokyo Art Museum, which actually proved to be more like a historical recreation museum. As we rode the escalator up to the third floor, we passed large painted persons of various economic levels in changing finery going from older, Edo-like styles to more modern, Victorian-influenced styles, to still more modern 20th century military and civilian styles. On the fifth floor, where you started the tour, there were various miniatures displaying the lay out of Edo and some of its important sections, with their source materials and further information displayed in glass cases along the wall. Down the escalator, life-sized recreations of the lives of various classes of people could be gawked at and passed through. We learned about the way that people made money, the way people used their living spaces, and the way people learned what they needed to know in life. To me, if felt a bit idealized, maybe even a bit fake, but as an incorrigible fan of fantasy and fiction, I found it more entertaining to enjoy imagining that this was how it really was, that people really lived like this, that life could ever be that simple.

Further along the pathway, the museum’s tone changed slightly as it spent more space talking about the way that life changed; how, through various stages, Edo became Tokyo as we know it today. Not negative, per say, but perhaps a bit sad? Or was it just me because I’d grown so found of the fantasy created in the first part of the museum?

At a 7-11 later in the day, I bought dinner. I set my selection on the counter and then pointed at the nikuman in the heated display and said, “これもお願いします。” I paid by waving my suica card. She then asked if I wanted the bun in a separate bag, speaking quickly in a noisy place. I felt panicked at the sudden rush of Japanese, only some of which I’d heard, and I spat out “もう一度?” I should have at least said, “もう一度言って”, and adding a “下さい” too. That would have been proper. After a pause, and an expression I took to mean confusion, her face hardened a bit and she said yes, I did want a bag. Then she handed me my bags with a pleasant enough smile. I practically ran away, almost forgetting to take the receipt she offered me.

June 1st

This morning I got to go on a walk with Forgash-sensei and Cloe, for the purpose of seeing the true Yanaka. We went South and West, turning down a main road that led to the road that leads to Ueno Park which I’d taken the day before, but we turned right at the Scai bathhouse. Eventually, we found a tiny pathway that lead between and behind the houses lining the main roads. We passed numerous cemeteries and tiny shrines, including a most interesting little shrine that was tucked in a tiny little triangle in between two houses, with lots of plants and moss covered stones, and a tiny little house on top of piled rocks facing inward, with just enough space in front to stand when you followed the tiny rock path to get inside and in front of the little shrine. If I recall correctly, it was a shrine dedicated to Fujisan. As before, I observed that nearly every house had potted plant gardens beside their doors. I also got to see some of the house’s niwa, or garden spaces, which were always lovely and well kept. One of the doorway gardens had many kinds of succulents in pots, with one hydrangea standing tall and colorful amongst them and a delicate and wiry looking raspberry or blackberry bush beside it. The ally way we were using wound and curved so much I nearly lost my sense of direction, and totally lost my sense of distance. There, we met several elderly ladies. The first greeted us, smiling cheerfully with an easy “Good morning”. When me and Forgash-sensei replied with “おはようございます。”, she adjusted easily, saying, “あ、おはようございます。” and grinned. The second woman we passed was looking at a garden that may or may not have been hers, and seemed to ignore us as we passed, but I paused to take a picture of a lovely little red and white flower on the far side of this garden. When I glanced up, she was watching me, so I smiled and bowed a bit, and she nodded a little. She didn’t seem angry, though her smile was very slight. The last lady was out watering her garden, and she smiled and greeted us in Japanese with energy. I get the feeling she was proud to be seen tending her garden… or she was just friendly. It dead-ended in another shrine with 4 or 5 planters with potted begonias in white, pink and red lining them and boxy bushes filling them out. This one, of course, had several very old and carefully shaped trees such as ginko and pine, and numerous fruit trees that might have been grapefruit. Its cemetery was off to the side and gated, and it had row upon row of tables set up with white table clothes under pavilions beside the pathway to the front entrance, but we couldn’t quite tell what they were for. In another shrine I caught sight of my first stray cats in Japan, and there were three of them. There was a tortoiseshell with a stumpy tail, the friendliest, a white and gray one, and a white and orange one. A dish for their food and a dish with water in it had been set down just inside the temple grounds, right beside the door.

Later this day we went to bousou no mura, a recreation of a farming village from the Edo period and a present-day self-sustaining community.

When we arrived, we intended to eat and then enter to park, but things didn’t go according to plan. We entered the restaurant and a short conversation occurred between the young man manning the cash register and Kim-sensei. It’s been said that the young man at the time was attempting to warn Kim-sensei away. But when the message didn’t get across, the young man took all of our orders. Shortly thereafter, when we all were settled, the manager personally came to inform Kim-sensei that they would not be serving us because they already had a large group coming. So, we all lined up to get our money back. The distress in the young man’s face was evident throughout this process. Kim-sensei was quite peeved and declared that he would never return. I had trouble locating my receipt when I got to the counter, towards the end of the line. The young man pulled out a crumpled receipt from a basket, and asked if I’d gotten a curry. I’d gotten the curry with shrimp, on top with an ice coffee, but I was the last one in the restaurant, stressed by the suddenly irritable air, and concerned by the fact that the group seemed to be leaving without me, so I said yes quickly, without thinking too hard about it, only to realize I’d shorted myself when I got the money back. I didn’t turn back. Later, after I’d entered the park, I found my receipt. It was suggested around this time that a reasonable business should be able to handle two large groups and serve us, and that perhaps the place just wasn’t into the idea of serving us.

Another interesting interaction was with a lady who led a craft making station. I made this little ornament that looks like a traditional barrel, which often held sake or shoyu, for Ronnie under this woman’s guidance. When I walked in, I asked the man out front if it was ok to enter, which perhaps led him to believe that I just wanted to watch, which was half true at best. He gave consent readily, and I watched three other people, two women and a young girl, make their own versions of the souvenir. When the lady in the center finished, I moved like I wanted to take her place, and when I thought I might be ignored, I said something along the lines of “I wonder if I can do that”. The organizer seemed to realize that I wanted to participate, and seemed a bit hesitant, but she asked if I wanted to try it, and I said yes. She warned me it might take 30 minutes, and I said that was fine, probably. Then she had me pay at the front of the shop and write my name to the side of what looked like a signup sheet. I had by now missed at least 4 warning signs. I thought I heard her say something about needing to wait, so I moved to leave but she stopped me. I asked if I could do it now and she said yes, then asked if I wanted to do it later. I told her now was better, because I was worried about my meet up time with the group. She hesitated, so I said it twice. She asked if she could instruct me in Japanese (Note: this may have happened a bit earlier in the conversation), and I told her I was fine with Japanese, probably, and she looked at me very surprised, and asked me, “本当?” (upon reflection, could this have been sarcastic?). I just nodded affirmation. Then we sat down and she said that we should do it quickly, and at least I heard that. It was said at least twice near the beginning of the crafting process. She then explained that the shop was a barrel shop and the ornament is meant to look like a mini barrel, made with the same kind of bamboo that they made into ropes and wrapped around the wooden planks of full-sized barrels. She also gave me the names of each level of the bamboo wrappings. Then she helped me through the crafting process using a lot of onomatopoeia and gestures, which I appreciated. At one point a bamboo stem came undone, and had to be redone and she actually made a sound of frustration, using a lot less care in choosing the replacement strand. But I did make an effort to work efficiently and quickly, and I wonder if she could tell, and was mollified, because she seemed to relax as we went on, till our comments as I finished were pleasant. She complimented me on my speed, and said I’d done well, and I made an effort to express that I appreciated her giving me her time. I groan now, looking at this experience, but hindsight is 20-20, right? As I was leaving, I caught snippets of conversation between her and a co-worker that made it clear she was meant to have gone on break, and that my appearance had cut into the time she had before her next shift.

The last interesting interaction was with a fellow in the train station. Our group had split up into groups along the platform as we waited for the train. I was with the central group, 4 of us, closest to the gate. We were talking, and he must have been watching for a little while at least because he broke into our conversation at a very small pause. It felt like an interruption, which surprised me. In English, he asked if he could ask us a question. I said “はい” quickly. Perhaps he thought I was saying “Hi”, because he repeated himself. I then said “どうぞ”. Without missing a beat, he went on in impressive, confident English to ask if we knew about the festival happening in the area, since westerners, especially groups of them, were rare around here. I told him we didn’t know, we were just going back after visiting bousou no mura. He then asked if we’d taken the bus to get to this station and I said we had walked. He seemed quite surprised by that, with big eyes and a “wow” which was the loudest word in the conversation. He then asked if we were staying in Narita. I started feeling like I was getting interrogated and hesitated, but told myself if was harmless info, and told him we were getting off in Nippori, which elicited another reaction of surprise. I wonder if he knew how expensive it would be. I had gestured when I’d said we’d be going to Nippori and he told me it was in the other direction. He also said something about going to the other side of the tracks to catch the right train, but as this proved false, I’m not sure if that was ignorance on his part or a misunderstanding on mine. He then told us a bit more about the local festival, which involved lots of candles. He cited a large number, either 3,000 or 30,000 of them, which are lit in a central location about a quarter of a mile from the station. Then the train carrying the person he was waiting for came and the conversation ended abruptly. I managed to tell him thank you before the crowd and the train noise interrupted and I wandered off to ask Kim-sensei about the correct side of the tracks to be on.

Bousou no mura was pretty nice. Ok, really nice. I got the chance to have soba sitting in seiza on a pillow in a tatami covered upper room with a window overlooking the village center. One thing off the bucket-list, among many on this trip. I didn’t quite know how to eat what I was served. I ordered tororosoba which came with the soba sauce in a cup, the noodles over a bamboo grate, and a cup of what looked like gruel and tasted like rice. Apparently, you’re supposed to add the gruel to the sauce to thicken it, then dip the soba into it. I ate it separately, like it was mashed potatoes or something, which was fine, if bland. They had self-serve tea and water, which surprised me, as that was something I had never seen before. Then I went to a sweet shop where I spoke almost all Japanese with the older lady and gentleman there. I was a bit nervous, so I didn’t speak very well, but we communicated. I kind of like the way people interact with me when I’m alone, when they aren’t ignoring me, anyway. This lady, for example, seemed to treat me a bit like a child, asking me simple, safe questions like where I was from and how long I’d been in Japan, but she was happy to talk to me. As a hostess, she engaged her two customers, often listening to my simple statements and then turning to the older gentleman for input. He didn’t talk directly to me, but he smiled and bobbed his head, and also politely listened to my childlike responses. Maybe it’s just the Japanese way to cater to the attention needs of a young girl. As someone who desires to move into uchi, I shouldn’t get used to it. I’m also certain that if I’d been in a group, that lady would have been a lot less interested in talking, or at least she’d have felt less pressured to engage me.

After that I made the ornament, that whole fiasco. Then I went for a walk through the wider grounds. It’s actually a large place, with several rice fields and vegetable gardens, even wheat and similar grains, tucked away between vivacious forests. I felt recharged by the nature and the quiet and scents of earth and water and plant life. When I was following a faint path through what appeared to be a garden, a small boy and his father passed by on the other side. The young boy said “変な人”, basically “That person is weird”. The father immediately chided the child and directed him onto the main path, disappearing quickly. Initially, I was inclined to assume that I had done something to inspire this opinion, but despite much contemplation, I can’t for the life of me offer an explanation, as I was doing precisely what they were doing, if alone. So either it was simply because I was a gaijin, or it had absolutely nothing to do with me, and I just happened to overhear.

I got to bang on taiko drums and sing in the trees (when I was certain no one was around) and observe what farm life is still like in Japan. It made me feel happy and energetic. Bousou no mura proved one of the highlights of the trip.

For dinner I ordered yakitori from a place near our ryokan, and it was ridiculously cheap and jaw-droppingly tasty. I also got hijiki (a small black seaweed, from what I understand) and ebitenpura. My voice began to disappear halfway through the day. I hope I’m not getting sick. I want to watch people on the train tomorrow.

June 2nd

Today we went to Shibuya to check out the famous depachika there and see Hachiko and Shibuya crossing. The depachika lies beneath a department store, as the name implies, and is filled with little shops all selling food and beverages. It’s like a clean, mini wet market. You can buy just about anything available in Japan there. While there, we bought lunch from various places. I bought sushi, a brownish boba drink that tasted like toasted matcha, and a little berry mousse cake. There was an area for people to stand around counter-tables, since eating and walking is rude in Japan, and our whole group spread out in little clumps around it. A fellow walked up to my clump, saying with his body language that he wanted the space between me and Preston, so I made a little room for him. He then asked me, in Japanese, where I was from. I didn’t hear him well the first time, so I asked him to repeat himself, which he did, in Japanese again. I found this surprising, since most people automatically switch to English if I don’t get it right away. I told him we were from America, and he asked how long we were here for and I told him three weeks. Around this time, we also established that we were a whole group, and that I spoke some Japanese. I needed to clarify that our trip was three weeks, not that we’d been here for three weeks, because the Japanese tend to ask about the later, not the former. He asked why we were here and I told him we came for school. He asked if we were transfer students and I said no, just studying here through the school. I’m not sure that explanation made sense to him, but I didn’t know the right words. At this time a woman in a suit and skirt with a suitcase joined us and he recapped our conversation to her. He then asked what we were studying, and I told him Japanese culture, which he verified in English, as though he wasn’t sure he’d heard me right. He then stated that the woman, who was quiet, was from the north end of the mainland. I had them explain the location a little more to me. The few words the woman spoke were heavily accented and I had trouble understanding, and apparently, she had trouble understanding my Japanese as well, for the man began translating both of our statements between us. All of this occurred in Japanese, so mostly he seemed to just repeat everything that she and I said. My voice was in and out, so maybe it was a noise level issue? The depachika was pretty noisy. Curiously, at one point I said something in Japanese and he said it to her in English, which she seemed to understand. I’ve realized that perhaps part of the reason I feel interrogated in these conversations is because I don’t ask enough questions. The next person to strike up a conversation with me, I want to take an interest in them as well.

Twice now, I’ve stood in a crowded place taking pictures, of things behind or above the people, and I’ve heard a Japanese person say “jiyuudesu ne”. Once I was walking in a garden at bousou no mura photographing the plants and a little boy said it to his father, the only other person around. Today, I had gotten a token photo of Hachiko and had squirmed out of the really thick crowds around him for some air. I started taking pictures of the intersection, when two young men walked by. The one nearest me made the comment, and the other just smirked before they had passed on out of view and earshot. Is it my camera? My clothes? My hair, which seems to grow fluffier by the day? Location?

I had to buy cold meds today. I stepped into the store and approached the man greeting all the customers. I stumbled through my first few words, struggling to use my voice and uncertain of the proper questions to ask in this situation, and he patiently waited till I managed to spit out, “風の薬は…” He then led me to a wall of cold meds and tried to ask me about my symptoms, but I had forgotten that word. While he looked around for another way to say it, another man in a white lab coat walked up and took over with barely a word spoken between them. The first man walked away quickly, looking relieved and visibly relaxing, though I hadn’t noticed his tension before. The lab coat fellow began asking me about my symptoms, using gestures, simple Japanese and a very little English. The gestures were especially helpful. I said that my throat hurt, I had coughing, and suggested that my nose was affected, but stated emphatically that I didn’t have a fever. He found that hard to believe, I think, citing the weather and suggesting that it was strange that I didn’t have a fever, after asking twice. But if I had a fever, I certainly wasn’t feeling it yet, and I insisted I didn’t have one, to which he nodded and moved on. He asked who would be taking the meds. He had to ask several times before I understood, then I told him it was for me. I wonder if he didn’t quite believe me, because he pointed out firmly that the meds he was recommending were for persons 15 and up, and he said this several times as well, till he got a firm “分かりました” from me. He then started telling me, in English, that I needed to take the meds 2 at a time, 3 times daily after meals. He asked if I wanted enough for 3 days or 5 days, and I said 3 to start with. He reiterated that it was for persons 15 years old and up, and I expressed my understanding. He checked me out himself. It cost just over $10 for 3 days’ worth. I tried to thank him profusely for his help, and he bowed very low as I bowed a bit to him. I was confused by this respectful, self-controlled bow. What did he mean by it? I nodded my thanks to the first person who helped me as well on my way out. I was wearing all black, a semi-professional long-sleeved button-up shirt and slacks. My hair was fluffy as all get out. My voice was clearly wrecked, though I thought that it may have sounded more like a smoker’s voice than a cold problem. Did he think I was with a criminal organization? With my gender, sloppy Japanese, nationality and age?

I’ve been watching the people on the trains. There was a man across the way who proved exemplary. Throughout today I have been counting, and in crowded trains, 8 out of 10 people are looking at their phones. This fellow, though, was interesting. Having neither phone nor book, he stared at the windows, ceiling and ads. But when the train got busier, a woman stood directly in front of him, and he couldn’t seem to decide where to look. His eyes constantly wandered till she got off.

June 3rd

Today we went to Tokyo Metropolitan University (TMU). We met Koko-sensei at the station. It was really nice to see her. It was hard to tell if she was happy to be in Japan or not. She does a lot more bowing, uses more frequent and more polite honorifics, and uses a higher pitched voice than she does in the States. She also holds herself in more, behaves more formally, and actually seemed a bit out of her element. But maybe that’s just more of her Japanese-ness showing. Is it effortful for her, or does it happen naturally, having been raised to it? She called me her best student, right in front of me, twice. The first time she was introducing me to Nishimura-sensei(?). The second time I was talking to Tamino-san when she walked up and I introduced her as my teacher. The second time, she followed up the compliment by noting that I had studying on my own, so her teaching didn’t have much to do with my abilities, which is all but a bald-faced lie, as I attribute at least 80% of my progress to her effective teaching. I said as much in another conversation. Is this how it’s supposed to work? It feels like I’m getting filled up and only trickling goodness and affection in return. It’s made weirder by the fact that she’s never been that complimentary to my face.

With my voice all but gone, it took an extra amount of courage to speak at all today, never mind in another language, but even so I had some good conversations with three Japanese students. The first was helping to organized the event. She is studying in Kenya for her anthropological research. She’s even learning Swahili. As lunch ended, she started cleaning up, and for a while she tried to continue the conversation at the same time. I offered to help, but she firmly refused, citing the fact that it was her job. Shortly thereafter, a fellow named Kotaro joined us and she seemed relieved, so we let her get on with her job while I talked with him. Is it a rule in Japan that you can’t just leave a person hanging, even if there’s something else you really need to do? I wonder if there is a gracious way to release someone from a conversation when I see that they have other responsibilities. This keeps happening. Is it polite to just wander off?

Kotaro is studying the military bases in Okinawa and their effects upon the communities surrounding them. The conversation was interesting, especially since we’ll be going there to study roughly the same thing ourselves shortly. At one point, I asked him if he thought the bases would ever disappear. He paused for a bit, contemplating his answer, and then admitted that it wasn’t likely. He said that it seemed like it would be good if they did, but realistically speaking it probably couldn’t happen. I privately thought to myself that I would have a hard time studying something that I didn’t really believe would change. Hence my troubles in most social science classes. I wondered how he does it.

The last girl I talked to was Tamino-san. She’s an anthropology major studying folklore, especially as it pertains to foxes, kitsune, and their unusual ability to transform into young women. She said that nowhere else in all of mythology do you find foxes that transform, and she’s curious about why young women, seeking the meaning or reality behind such myths. Sensing a passion, I eagerly asked her about the things she’d found or read so far. She told me that she hadn’t come to any conclusions herself, but she’d read a lot of different theories and opinions on the subject. Around this time the whole group began a tour of the campus, walking through their wonderful little forest to the campus’s private shrine and back. We wandered across bamboo bridges and through narrow walking paths. The local shrine was supposed to house a deity who lacked a form. The place was in the middle of being renovated, supported by local worshipers. Slowly, my conversation with Tamino-san turned to plans for the future. Tamino wasn’t sure when she’ll graduate, but she thought that when she did, she would get a job at a company, go for the lifelong employment thing, if she could get it. We also talked about dreams. I made the statement that I thought dreams were a bit dangerous, thinking back to my earlier conversations and considering my own life, which always seems to make the most progress when I put actionable goals just a few steps ahead of me, not worrying too much if it leads me to the exact dream I have envisioned because I am confident it will lead me where I need to be. She was quiet for a bit, then asked me why I thought that, and I tried to explain, also pointing out that a lot of people waste their lives chasing fantasies, thinking about my parents now. But, I added, people also waste their lives never doing anything they actually care about, so “it goes both ways” was my conclusion. I don’t think she quite knew what to do with that, because she was quiet till the conversation took a new turn. When we entered the shrine, she bowed beneath the tori (the tall gate in front), and she encouraged me to do the same. Somehow, I really did feel like I was intruding, and was tempted to say something along the lines of “お邪魔します”, asking her if she ever did things like that. She said she did, though she acknowledge that she was amongst the minority that takes shrines seriously. Along the lines of future plans, I asked if she planned to marry. She said she didn’t really plan on it, not if she could support herself. I told her I didn’t plan on marrying anytime soon, mainly because it’s too scary right now. I wonder if she was put off by my honesty or something, because she made a tiny little frown, and quietly nodded saying “そうですね。”, which isn’t necessarily agreement. Most of our conversation, we walked side by side or slightly staggered, but we rarely made eye contact. Often, I would finish a sentence and then glance at her, trying to gauge her reactions. I think she did much the same. This felt much like the way me and my best friend talk when we go on walks together, so it wasn’t uncomfortable to me, but I wonder how she felt about it. The day before I left for Japan, my friend had told me that she tended to form fast, shallow relationships with seemingly everyone, while I tended to be more selective but then worked to form deeper, more lasting connections. This made sense to me, because I had to learn to make any connection consciously and effortfully, so I never really learned why or how to make time for the shallow relationships. I think this attitude may be both a blessing and a curse in Japan, especially since many of the books I’ve read on Japan state that the Japanese are a lot like me in this respect. But I think I need to be bolder and more interested in finding time for the loosely established connections outside of the formal settings where they were first formed. Like with my best friend, the relationship didn’t really take off till we started making time for each other just to spend time together, instead of just seeing each other in church and at shared activities.

The only time Tamino-san and I turned to face each other as we talked was when the group stopped and waited for the tea ceremony club to get ready, but the dynamic had changed because Koko-sensei joined us. We talked about the weather and my language ability. It felt more formal, again, even if Koko-sensei is friendlier than I am.

The tea ceremony was awesome. I had watched a few on Youtube, but getting it first hand was special, especially since I had an honored position. I get the feeling that that was not really my place, but as I didn’t have any say in the matter, I chose not to be bothered by it, merely making an effort to be as self-controlled and proper as I knew how. I was fascinated by the pride that the club expressed in their tools, even going so far as to display the two nicest bowls, the container holding the matcha, and its scoop after the ceremony was over. From what I understood, they were handmade, works of art inspired by natural beauties like the pattern of a turtle’s shell and a crane in flight. They also wanted us to pause and admire the special wall. I wanted to call it a kamidana, but I don’t think they went that far. Its décor was simple, just a wall hanging with flowing script and plastic flowers in a lovely vase, so I feel that I really missed the significance of it, since it wasn’t a kamidana.

June 4th

Today I hung out with Junpei, a friend I had met in Denver through work. We had met the night before to eat and talk about what exactly we wanted to do today, and we’d spotted Forgash-sensei at the sushi place. She’d made a recommendation on a fish, which proved quite tasty. We also passed her today on our way to the train station, and I greeted her casually. He found out, after we’d already walked away, that she was my teacher, and he was perturbed. He said, “so she was your teacher” several times after that. I think I need to be careful about that; more up front, maybe?

We went to Meiji Jingu, which holds a lovely shrine and supposedly houses Emperor Meiji and his consort, with an ancient forest surrounding. There were two particularly large old trees growing into each other, looking like one massive tree from a certain angle, which stood beside the shrine. When you got closer, you could see the separate trunks and a rope with hanging, folded papers on it strung between them. The trees, if prayed to, are supposed to bring happiness and permanence to a marriage. I liked the symbolism, even if I couldn’t hold to the misplaced reverence. There was also a broad lawn in the center of the forest, where one could enjoy the grass and the sun. I itched to play and run and sun-bathe there, but I somehow couldn’t with Junpei there. He said the place, the lawns and the forest, didn’t feel like Japan to him. Afterwards, we wandered through Harajuku, which he said seemed to him to be a very young Japan, a place for young people, though he’s still in his mid-20s. He referred to the people there as “若い者” or “young’uns”. Maybe it had more to do with their attitudes and lifestyles, rather than actual age differences. Then he treated me to ramen. In fact, that entire day he insisted on treating me. I had a bit of a hard time accepting this, but tried to graciously accept his generosity (if that’s the word for it), as I felt that was the only proper thing to do as a guest. We then went to see the Tokyo Tower. We explored the mall beneath it, and he insisted on getting me a souvenir. “Is it really ok to accept that?” I couldn’t help but wonder, but he would not let the matter drop despite my resistance. I got a decent shot of the Tokyo cityscape from the fifth floor of the mall. I told him I needed to be back around 4pm, which is good because I was fading fast on the train ride back. Once I got to the hotel, I took a nap till about 8, when I got up to eat, take my meds and do my laundry.

June 5th

Today we will go to Hakone and enjoy an onsen, but I wanted to focus on culture shock in my notes today. I’m probably one of the last persons who still has jet lag, so that may be affecting my experience, but I’ve been ill-rested for months now, so I don’t think it’s affecting me much. Day 1-3 (for me, it’s 2-4 for the rest of them) I was emotionally drained and mostly just worked to absorb everything I could without real evaluation, kind of going through the motions in a constant fog. Some things seemed different, but not strikingly so. It makes a difference, I am certain, that I’ve been to China twice before this. Certain things would be very different, but for the fact that I’ve seen and adjusted to them before in China, like the bathrooms, and a limited connection to the world back home. Some other examples are: The market centers, the walking, the trains, the narrow streets with the too-friendly-for-comfort cars, the language barrier (which is actually a lot less problematic here, not only because I actually speak some Japanese, but also because many of the stores have people who actually speak some English), personal space differences, the foreign ideas about natural beauty in parks and gardens, the overabundance of advertisements, and the moisture haze. These are all things that I’ve actually experienced, and even grown fond of, before coming here, so there were easy to recognize and accept here.

I’m having a bit of a hard time with Kim-sensei. It’s nothing big, and no confrontation has or will occur, but I disagree with his worldview on multiple accounts, and I don’t like the way he gets when someone messes up. It reminds me a lot of my Japanese boss, Toshi-san, and having been on the receiving end of that… It’s not pretty, and it’s not necessary. He also seems to derive a bit of pleasure from antagonizing people, which is actually a bit amusing to watch, but also irritating. Maybe that one gets to me because he reminds me of myself?

I’ve actually been cold for a lot of this trip. I’m disappointed, because rainy season or not, I was told to expect humidity and heat, two things I happen to enjoy.

My body aches. When I’m moving, it’s easier to ignore, but today carrying my backpack through train stations and sitting for hours on the trains, it aches, and it’s dampening my mood (in case it wasn’t already obvious).

Is there a difference between homesickness and culture shock? I’m a home body. I love the life I’ve created for myself there. I miss my cats, and my friends, my church and my books. I miss the dry sunny weather we get in summer, and my little struggling garden in the backyard. I’m also a creature of habit. I miss waking up at the same time every day, going to bed in the same bed, at the same times, after watching some anime or reading some fantasy. I miss talking to my roommates when they get back from their activities, hanging out in the kitchen sharing the day’s stories. I miss my car, the quiet alone time I get there. I miss being able to sing anywhere, anytime I want. This is homesickness, and it started yesterday. Does that count as culture shock?

June 6th

Yesterday, we arrived in Hakone around noon. The train ride was long and I suspect that my fever had begun at that point. I exited the station and observed that the town looked much like the more touristy places in Tokyo. Lots of small shops with high prices, and Japanese men and women in old fashioned clothing asking passersby, “いかがでしょうか。” We ate lunch. I got to help with the orders and payment process because the servers didn’t speak much English. I accidentally left my phone there and had to go back to get it. The smiles of the server and cook looked like they were quietly laughing on the inside, but I was laughing too.

Then we went to Tenzan, a fabulous hot spring resort. I showered on a stool then stepping into a wooden jacuzzi called, when loosely translated, the heater-upper, which was really hot. My skin was instantly red, and even I could only stand it for a minute or two. Now nicely heated, I didn’t feel at all uncomfortable in the air as I walked over to the next pool, a much cooler one, right at soaking temperature, which was lined with natural stone and was filled with so many tiny bubbles the water was milky. After I’d cooled again, I went in search of a warmer pool, and found one at the top of some steps, overhung by sweet smelling Russian sage which had dropped many of its little yellow flowers into the pool. At the back of the pool was an actual cave where the source of the spring was, hence its heat, where you could do a hot spring and a wet sauna at the same time, but I feared overheating, so I just popped in and out of the pool at its end, alternately heating and cooling myself. Forgash-sensei was there, and she started up a fun conversation with a Japanese lady there, which they graciously allowed me to listen in on, but I don’t remember much of it. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was making my fever worse. The dry sauna I baked myself in after that definitely didn’t help either, though you’d think that whole “gotta sweat the fever out” thing would apply here. Maybe it was because I napped for too long in the cooler upper rooms when I got out.

I was dizzy and bleary when I got up, but my pride reared it’s ugly head then. Not only did I refuse to tell anyone that I was not feeling well, but I insisted on racing a fellow to the bus stop, then walking with Sensei halfway down the hill to a bus stop much nearer to the city center. Never mind the blistering headache, never mind the fact that I couldn’t remember the last time I was so close to literally collapsing where I stood. I wanted to seem fine. After a rough night spent sniffling and fighting the beginnings of an incessant cough, I felt slightly better in the morning, and after walking to the store and back decided that surely I was past the worst of it.

This day we rode a pirate ship back and forth across the grand lake, and learned about a trail used by the Daimyo, who were forced to commute back and forth from their domains to the capital on an annual basis during the Tokugawa era. We even went on a long hike along a stretch they used, called ishidatami, or stone tatami, though the path was anything but flat, the stones uneven and mostly round, so it seemed a bit misleading. We followed it all the way to a tea house, where we got to try amazake and two different kinds of mochi. All of it was super filling and I really needed water (my fever was even making me a bit nauseous), so I couldn’t finish, but it was cool nonetheless.

June 7th

Today, when I woke up, I was most miserable. Maybe I really am experiencing culture shock, like they keep warning us about. I haven’t felt particularly bothered by the differences in Japan, the places we’ve been staying, or the group around me, but despite how hard I push myself each day I’m sleeping less and less, eating less and less, I’m not getting over my cold like I’d hoped, and my emotions have gone out of control. This didn’t happen in China. The first time I went, there was about 2 days early on when I got really homesick, even to the point of depression, but I talked to my friends about it (it helped that I was with friends on that trip) and I was fine. I slept and ate very well the whole time. On the second trip, China felt familiar and I was fine the whole time, even though I caught a cold then too. I was over that cold in 2 and a half days, unlike the poor lady who I caught it from, who was sick the entire trip. So what is it this time? I don’t even know. Spiritual warfare?

The pain was so bad this morning I couldn’t stop crying. There was an incredible pressure in my ears, I had a blistering headache, and the fever was at the point of body chills, aches from head to toe, shaking, exhaustion, weakness and dizziness. The cold had moved into my nose a few days ago, so I was constantly dripping and sniffing, trying not to look utterly disgusting. I was given Zertec and Ibuprofen, so by the time we got to the station the pain had faded enough that I could stop crying and my nose had reached manageable levels. For once I was glad the Japanese tend to ignore what they don’t want to see. It was like they couldn’t see me at all, and that suited me fine since I felt the complete opposite of presentable. My teammates had a lot of pitying glances to offer, but that just made me more miserable and lonelier, somehow. They just didn’t know what to do, I think. Shayla and Leah asked if I was alright, and John offered to buy me ice cream, citing that my trip had been harder then everyone else’s on multiple levels. I told them I was fine, that I didn’t need anything. I acted like I wanted to be left alone. It was here that I realized that even though I seemed to get along with everyone here, I didn’t trust any of them. Can I change that?

I bought some cold meds, the strongest in the store, at the mall inside the station, so by the time I got on the train I was back to feeling a little sick instead of very sick.

The Shinkansen was amazing. It was literally breathtaking to watch them race by, making noise about the quality and volume of a super-sized air conditioner. It was raining pretty heavily, so the trains had a halo around them and crackled with electricity where they connected to the wires above them. Inside they felt like spacious airplanes, with semi-comfortable seats in rows, overhead storage, pulldown curtains on the windows, bathrooms in every car, and personal vents that you can close if you want, which I did, of course. As we moved out of Hakone, the scenery changed a bit. The towns became more rural, the terrain hillier, with smaller towns built around the hills rather than on or into them. I managed to sleep a while, since the pain was gone. We arrived in Kyoto, where the roads are bigger, cars more numerous, the streets are straight and lined with old buildings sitting comfortably beside new apartment complexes. You can tell this place has a thriving tourist industry. I passed a restaurant with an enormous crab on it’s front, and near our hostel another restaurant was built to look like a large, ramshackle shanty which calls itself Bikuridonkii, the startled donkey. When we got to our hostel, I wasn’t surprised to find a modern, almost hipster place. I actually liked it a lot. We had bunks and could pull curtains all the way around, sealing the space off. It’s clean, and has great facilities. I can do laundry for free, and they have a kitchen area where we can make meals and get coffee (instant though it be) anytime we want.

While the rest of the group went shopping, Kim-sensei and I split off from the group to go to the clinic. The buses here in Kyoto seem rougher, and are way noisier than the trains in Tokyo. Mothers with children are one thing, and both examples that I saw were quite successful at quickly calming their upset children for the most part. But there were at least three groups of young people who made no effort to be discreet. The first group seemed to be tourists, because they were young, but they didn’t have uniforms on. Maybe that actually indicated the opposite? All the school groups I’d seen in train stations at least had uniforms on, and were always accompanied by adults. There were 3 or 4 of these young persons, and I’m not totally sure what they were doing because I was trying not to pay attention and they were speaking very quickly, though I am pretty sure they were mocking some other people on the bus. The second group was a mix of guys and girls, about 5 or 6, again, high school aged at a guess, uniformed. They seemed excited, and even though they weren’t obnoxious, they weren’t using indoor voices, which is what I’ve come to expect in Japan.

On the ride back to the hostel I encountered the largest, loudest group I’d seen yet. They were all girls, in school uniforms (I guessed middle school this time), and based on the way they returned my glances, it was almost like they were daring any outsider to say something to them. No one did, of course, not me, not Kim-sensei, not the older ladies near them, and not the bus driver. At least, I didn’t see anyone do so.

When we got off at our bus stop, Kim-sensei had to ask directions. In the first shop we stopped by, which was literally just a few doors down from the clinic, the single customer service representative in there responded to Kim-sensei’s questions with an abrupt “知らない。” My jaw almost dropped at the casual dismissal and rudeness. It was an upscale accessory shop, and he knew we weren’t customers, but still. He was middle aged and overweight, relaxing like he was bored in his chair, and he barely moved the entire time we were there. The older lady we found a little further from the clinic in what seemed like her aging family business, with cardboard boxes along the walls and cracking flooring, was much more helpful, and offered us a polite smile, though she spoke very casually. Is it Kim-sensei’s influence? He keeps his sentences very short, but to completely unknown service representatives who might help him get to his destination sooner he can be fairly polite.

Perhaps this is why I found the behavior of the staff at the clinic so surprising. Their smiles felt a lot more genuine, they were flawlessly polite, even to me with my flawed Japanese. They acted like they were happy I was there and eager to see me healthy again. This showed in the way they patiently waited for me to fill out a surprisingly simple health history and basic personal information form; the way they carefully explained what I should do in the doctor’s office, and the way they all, to a man, told me to take care and get better. Maybe that’s just what they’re told to say, but somehow, coupled with those smiles, it helped me relax, even though I generally hate hospitals, doctors and medications, and being in a foreign country should have made it worse. The doctor was a bit different. He was polite, but like most doctors, he gave off the impression that he’d seen too many patients to care much about any one. I was pleased and a bit embarrassed when Kim-sensei told him he could talk to me in Japanese. The doctor’s eyes widened a bit and he asked “本当?” He sounded skeptical. But after that, he gave me simple commands in Japanese, though he spoke very good English, which he used for longer questions and statements. But he was respectful enough, even if he irritated me a bit when he asked, “Do you think these symptoms are worse than a regular cold”. It turns out it really was just a bad cold, but I’ve never experienced anything like it. I appreciate the fact that he ordered a blood test when he didn’t find anything, just to be sure it wasn’t bacterial. It made me feel that at least he took what I said seriously. The men in the waiting room seemed to find me an oddity. Some effortfully ignored me, but a few others stared. To them, I nodded politely and smiled a bit, but I was feeling sicker again, and tired, so I did a fair bit of ignoring myself.

When we got back to the hostel, a potluck was in progress. I chipped in, and helped myself to nearly everything, but I wasn’t able to eat much. That night I spent what felt like half the night coughing.

June 8th

I began encountering financial issues around this time. I couldn’t do the first activity of the day, which was a temple grounds, but Forgash-sensei said the next one was mandatory, so she loaned me money. I’d already had to borrow money from Kim-sensei to pay for the doctor visit yesterday. Pride or no pride, I’ll have to ask my dad to help me out. He’ll probably be happy about it anyway.

It was drizzling today, so people had their umbrellas out. I noticed that people made a real effort to avoid touching other people’s umbrellas with their own, as that constituted an invasion of personal space.

Next we went to Kyoumizudera, or clear water temple, which sits high on a hill looking out over the gion and central Kyoto. It involved a lot of steps because the whole complex clings to the hill side. The main temple was actually quite dark inside. I pressed through the crowd, lingered to watch the people around the incense burner, passed through a hall lined on one side by Buddhist figures behind screens and glass and on the other lines with row above row of candles burnt in memory of lost loved ones. As I passed out onto the other side, I followed the side walk up to another smaller but more colorful temple, where a line of monks sat moaning out their respectful syllables and bowing periodically, led by a singer with a beautiful voice. As long as I watched, they were there. I wondered how long they could go at it. Unlike meditation, which I think I could do for quite a while, this activity seems like the sort that would drive me up the wall in just a few minutes. I followed the path as it swung into the forest, past gravesites, and then swung back towards the main temple but lower down. There I passed a fountain, a natural one I am told, with 3 dragonhead spouts and a pool below, with an astonishingly long line of people waiting to walk up the steps, take a long-handled scoop, and catch some of that water to drink from their hands. They say that you can add years to your life if you drink this water. I got the feeling most people were really hoping for a better life, not necessarily a longer one.

After this I wandered into an area where a whole bunch of small shrines stood clustered together, with little shops selling the religious paraphernalia, of course, all claiming to grant various wishes. There was a place here where two stones lay a few meters apart, with those ropes and folded papers wrapped around them, where it is said that if you can walk with your eyes closed from one stone to another, you’ll have a smooth love life. I tried it out and got off course, despite Forgash-sensei helping to clear the crowds and offering advice. Near there, there was a small Buddha of which it is said that if you pet his head, he’ll grant you any wish. I was again bemused by the give and take attitude of the religion here.

Later, I was walking by myself in some of the lesser populated streets on the grounds. I can’t help it, I need breathing space after so many crowds. I had put my jacket, a gray and black wool long one, on over my purse. I was wearing all black clothing, as usual. As I walked, I adjusted the coat to pull the side hanging over my purse closer too me. I realized just as I did it that the movement was very similar to the motion of an action film’s protagonist/antagonist checking his gun and/or making sure it was concealed. In that same moment, I passed a Japanese man walking the opposite direction. I think my expression may have been a bit tight as well, because I was peopled out, sick and tired, and feeling spiritually attacked. As I passed, the man did a double take, and continued to watch me as I kept walking, craning his neck around after I’d passed him. I think I may have freaked him out. Did he think I was armed?

Soon after the group met up and we wandered through the gion, passing though packed main thoroughfares, then taking some back streets for fun. Seeing the backside of Kyoto reminds me of the real effort the Japanese put into their front image. In the back, the effort isn’t the same, as you can kind of see into the reality behind the pleasant face, not bad, just less put-together. We spotted some Maiko and got some good pictures of them. The difference between them and the Japanese tourists wearing rented kimono wasn’t just in the effort put into their hair and dress, but in the way they carried themselves, and the way they tried to lift their heads with pride under the attention of a crowd. We also caught sight of a full-blown Geisha, but she was far away, and we were warned away by a policeman, so we didn’t get a good look at her.

Then we had to all but run to the restaurant where we had super traditional Japanese food, centered around the various and sundry ways you can prepare tofu. It was delicious and exotic and fun, but there was so much food I couldn’t finish, which I was sad about. I really wanted to take the leftovers home, but somehow that didn’t seem like the thing to do there. I think we made too much noise as a group, but it had been an exciting day. I was coughing a lot too, which definitely didn’t help. They said something along the lines of “外人にはしょうがないね。” I’m pretty sure I even caught them glaring once.

June 10th

On the bus today I asked for a seat with my eyes, glancing around for a space, and a lady was kind enough to scotch over for me. I sat down gratefully, but it was a tighter squeeze than either of us expected. “ありがとうございます。” quickly became “ごめんなさい。”, both of which she refused to respond to. Two stops later, a single seat opened up closer to the front, and I quickly moved there. I didn’t look back to check, but I know I made the right move.

This morning I had to stop by the bank to get the money my dad had given me. I left before the rest of the team, got the money, then waited for the team in front of the station. As I wandered around the station people passed me calmly, glancing occasionally. A child pointed at me and the father casually replied. I was still sick, making my legs feel weak, and probably feeling a bit pugnacious as well, so I squatted down with my back against a pillar directly in front of the station. People had to pass me to get in and out. Now, not a soul that I observed gave my huddled figure so much as a glance, positive or negative. I think a couple people accidentally caught me in their pictures of the station, but they paid no notice. I suspect this is how people here prefer to react when something is wrong. Like an extreme version of “out of sight, out of mind” or “is it there if you can’t see it?”. Basically, it’s easier than having to deal with it, and no one gets dirt on them if there’s no negative reaction. I’ve seen this often enough.

When the team got to the station, we all went to Nara. Once there, we immediately began seeing deer. They wandered free about the city, petted by scores of people, hunting for the senbei that people are allowed to buy and feed the deer. Despite the numerous signs warning people that these were not tame deer, I don’t think any of us got tired of petting them. They definitely proved a highlight for me. We also saw several shrines, one of which houses the largest bronze Buddha in Japan. It’s the second reincarnation of the statue, as the first was at one time melted down for bullets, and at least the third reincarnation of the shrine housing it, but I still think my teachers’ pursuit of authenticity would threaten to deprive me of the simple pleasure of a great and interesting sight. Who cares if it isn’t the first one? They focus on the inaccuracies of the stories and histories, but I’d rather embrace the spirit of Japan that creates its history and its retellings. I’m feeling a bit hostile today, I think. Or it’s a lingering effect of the alcohol?