A short story by Rayanne Robison.

In a certain place where the hills are fertile and the sky is wide, there lives a shepherd. He has one hundred sheep, and he loves them. I am his son. I grew up tending the sheep, just as my father did. Maybe one day I’ll be as good as he is.

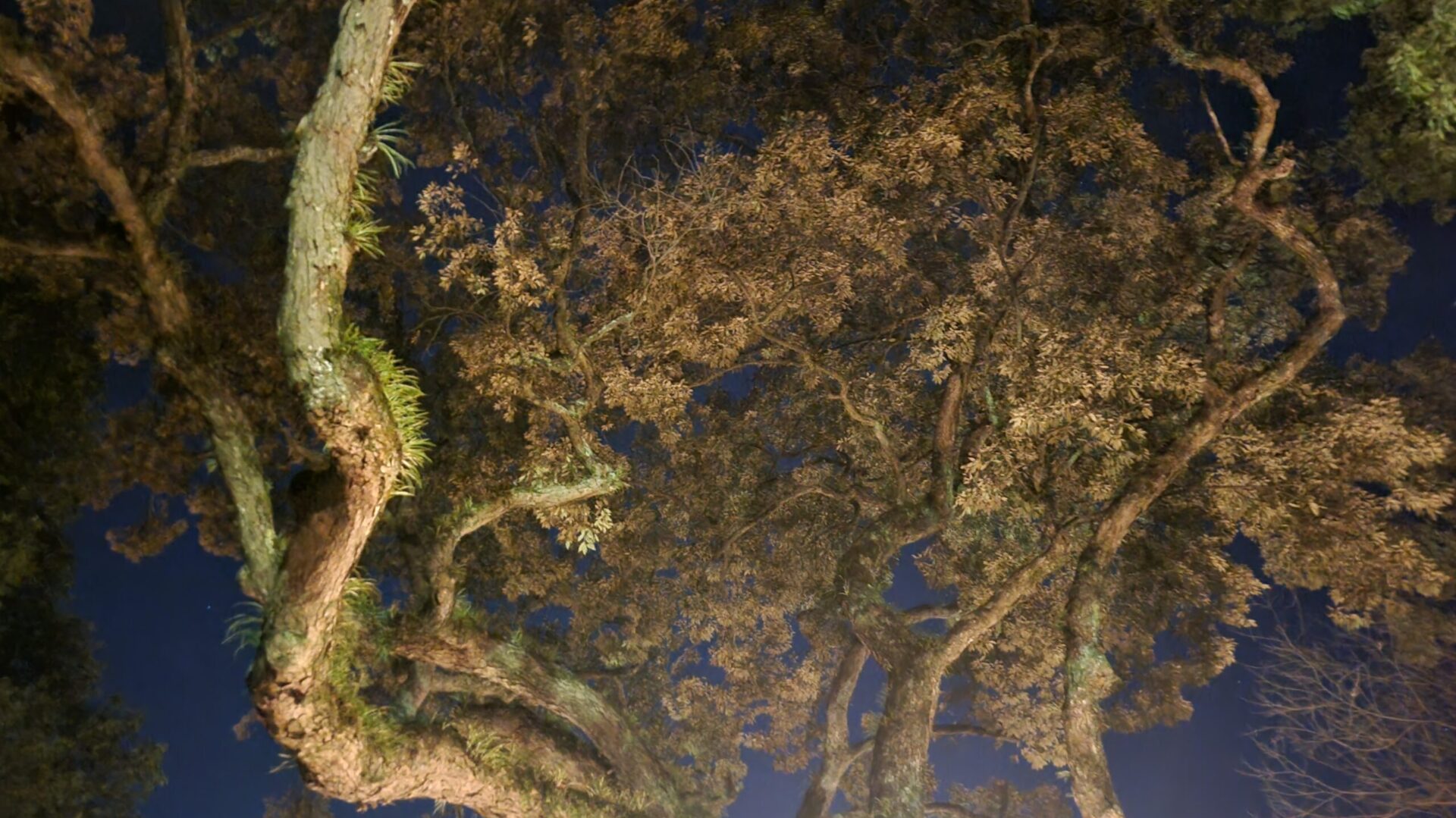

One day, my father and I were letting the sheep graze in a wide field some distance from our usual spot. I lounged in the shade of a scraggly tree, watching to make sure the sheep didn’t wander too far, and my father was on the far side of the field. For the most part, the sheep don’t wander. They know my father’s voice, and come running when he calls. They know they need him.

But there was this one lamb who, by virtue of his youth or rebellious nature, always tried to wander away from the pack and my father, and it was almost constant work trying to keep him with the rest. This day was no exception. I watched as that stubborn little lamb inched away from the herd, trying to act nonchalant by nibbling grass here and there, as though, somehow, I wouldn’t notice or know his intentions.

I watched him for a while, seething. He made my job hard, this lamb. When it was quite clear that he was no longer moving in the same direction as the pack, I called out to him. “Get back here, you. Yes, I see you. There are wolves out there, you know; wolves and rocky cliffs and hidden valleys and rushing waters and poachers. Stay here, where it’s safe, if you know what’s good for you.” I said this often, though of course the lamb never listened. He barely heeded my father’s voice, and the sheep knew his voice much better than they knew mine.

All at once I loathed that little lamb. If that lamb had its way, it would have me chasing it back towards the pack for the rest of the day, dancing this way and that in the heat of the day, clearly determined to run towards the dangers I warned of no matter what obstacle I could muster. The whole season had been like that. My legs were tired every day, my face sunburnt and sweaty, and each day I was a little more irritated and honestly hurt by that lamb’s stubborn refusal to acknowledge my words or my efforts.

“I’m done,” I thought to myself. “I have 99 other, sensible sheep to watch. If you’re so determined to go, then I’m not stopping you.” As that little lamb continued to wander farther into the hills and out of sight, I looked away.

That evening, as my father herded the sheep into their pen for the evening, he suddenly glanced around in concern. “Where’s the little one?”

I froze. I hadn’t considered what I would tell my father, or what he might think, but I immediately knew he would not approve. I couldn’t tell him. I glanced around like I was looking for the lamb then said, “I don’t know.”

My father grew agitated, and hurried the rest of the sheep into the pen. He turned to me, fear quite plain on his face. “Watch these. Don’t let anything happen to them.” The he turned and ran back towards the far field from which we’d come.

I was astonished. My father had never left the herd’s side before, not for anything. He’d been married to my mother right next to the grazing sheep on the open plain. The night was falling, and sometimes wolves or bandits would attack at night. As I built a fire, a deep anxiety filled me. “What will I do if something happens? Can I protect the herd?” A little voice reminded me, “You’ve already abandoned a member of the herd once.” I told the voice to shut up and checked my weapons.

My father hadn’t said anything, but I think he knew that I’d let the lamb go. He was disappointed in me, I was certain. That’s why he’d warned me not to let anything happen to the rest of the flock.

But as the night dragged on, at a time when I should have been getting very tired, I found myself getting jittery. The danger to the flock in a pen at night was real, but it was nothing compared to the danger to a lone man in the middle of nowhere at night. All the dangers I’d warned the lamb about were just as applicable to my father as he stumbled around in the dark without light or weapon. His staff and sword lay beside me as I hunched over my little fire just a little way from the pen.

Why would my father risk life or limb, and in fact the safety of the rest of the flock, for that one stupid lamb? Much I as I might wish for it, there was no great mystery. My father loved that lamb, and would risk everything, would in fact sacrifice everything, to save it.

Why he loved that lamb was a bit more mysterious, at least to me. It was stubborn, rebellious, and a constant pain to deal with. No matter what we did, it didn’t seem to get through. “But my father would never give up on that little lamb”, the little voice told me. That thought settled like a rock in my chest, knocking roughly against the cold fear that was growing as my father’s absence lengthened. It occurred to me then that just as he had never left the herd’s side before, I had never once been apart from him either, and the distance felt longer and colder because of my guilt. I hadn’t just betrayed the lamb or the herd, I had betrayed my father.

So, I sat hunched and shivering in front of the fire, teeth clenched and fists wrapped miserably around my knees, while the sheep settled down to sleep and the night strangled the light out of the world. The moon rose, but it was just a tiny sliver, cold and cruel and useless, while my heart sank beneath the two black voids of fear and guilt.

In the deepest, stillest part of the night, perhaps an hour before dawn, I heard the howl of a wolf and sprang to my feet, weapon in hand, shaking like grass in a fickle wind. I stood that way for a long time. But if his companions replied, I didn’t hear them, and after a while the silence and stillness forced me to settle back into the tense crouch, a small mound of darkness beside a small flickering light.

When the sun began to rise, I stood stiffly, and let the 99 out to graze, but I didn’t let them go far, staying in sight of the pen. I couldn’t lose the tension in my shoulders or the nausea in my stomach or that frigid stone in my chest, and now weariness made my body ache and my vision blur. But I forced myself to stay alert, walking around the herd in slow circles, refusing to let them move towards fresher plains, though they pressed me.

When the sun stood high in the sky, beating down on me, I caught sight of a shadow moving towards me, down a hill to the north. I cried out, but I couldn’t leave the herd, so I just stood there, shaking, while that stone in my chest grew, and the shadow slowly developed into the shape of a man. When he got closer, I could see he was carrying the lamb.

I wanted to be relieved, but the stone just got colder and heavier. I pressed a fist to my chest, but it didn’t do anything about the weight there. I stood in silence as my father gently placed the weary lamb in the pen and sat petting it for a moment.

“You wandered very far this time, huh. You must be weary. Rest a while.” The lamb set its head down on his knee. My father bent and gently kissed the lamb on its head. “I’m so glad you’re safely back.”

I stood there, silent, the stone heavier still. As my father slowly stood and left the pen, I could see the trials of the night still clinging to him. He was cut and bruised in a dozen places, his feet and legs were wet, his face dirty and haggard. I clenched my teeth and bowed my head, but nothing could stop that warm, stinging liquid from running down my face and dripping from my nose and chin.

My father loved that lamb. He had told me to love that lamb, but I had let it go, knowing it would not willingly come back, knowing it could not survive alone in the wild. I had given up on that lamb. How could I?

I wanted to tell my father the truth, to tell him that I knew I’d messed up, to tell him I’d never do it again. But through the pain in my chest and the tension in my throat I couldn’t manage it. All I could manage was “I’m… s-sorry… I’m so sorry.”

Before I could go further, I found myself wrapped up in my father’s embrace. He held me tightly, as I shook and wept and leaned on him. He kissed my forehead too. And he said, “I know. I forgive you. I’m so glad you’re my son, and I know you’ll do your best.”

I love it!